HERNIA PRINCIPLES: WHAT GENERAL SURGEONS CAN TEACH US ABOUT PROLAPSE REPAIR

The Hernia Hypothesis

Gynaecologists are beginning to articulate that prolapse is a form of hernia. I want to explore the implications of that possibility in a little more detail.

Hernia is the protrusion of an internal organ (usually small bowel) through the muscular wall of the body cavity, usually occurring at a site of natural weakness.

The pathogenesis of hernia has two components.

A mechanical event: namely, a ‘site-specific’ tear in the transversalis fascia, and

A metabolic event: namely, secondary (acquired) degenerative weakness in the connective tissue adjacent to the initial tear. Such degeneration in collagen quality inevitably occurs when ligaments not involved in continuous remodelling under the influence of body forces.

Likewise, prolapse is the protrusion of an organ (uterus, bladder or bowel) through the vaginal fibromuscularis, usually at a site of childbirth injury. It is also has mechanical and metabolic components.

The mechanical event is a group of ‘site-specific’ tears in the endopelvic fascia, and

The metabolic is an acquired collagen weakness in the endopelvic fascia. Connective tissue that is not exposed to the continuing remodelling forces (as occurs in a functioning suspensory hammock) display abnormal levels of lytic protease enzymes. Collagen turnover, as indicated by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity is up to four times higher in prolapse tissue (Jackson et al. Lancet 1996.347:1658-61. Moali et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 106 :953-63. Phillips et al. BJOG. 2006. 113: 39-46).

General surgeons have been able to reduce the failure rate for inguinal hernia to about 2%. The main vehicle of this success has been an adherence to a group of rules called the “Hernia Principles”.

We postulate then that these same “Hernia Principles” will help gynaecologists to improve prolapse repair outcomes.

The History of Hernia & Prolapse Surgery

1. Ancient Times:

As long ago as 400 BC, hernia and prolapse were well described, notably by Hippocrates in ancient Greece and Celsus in ancient Rome. However, the pathogenesis was not understood, and nobody envisaged an effective surgical cure for either problem. Physicians had nothing but ineffective medical and occasional primitive operations for the next 1800 years, from the time of Hippocrates to the beginning of Elizabeth I’s reign. Such as the cast iron girdle excavated from an archaeological site at Llandough in Wales. In this same era, women with prolapse were managed by being suspended upside down or by wearing a half pomegranate in the vagina as a pessary. Pessaries were later made from gold & silver, then from rubber.

Basically, nothing much changed until the end of the Dark Ages.

2. The Herniology Era:

The second era began during the Renaissance of the 16th and 17th centuries, when interest in hernia revived and some isolated (but notable) advances were made.

The first step on the road to modern hernia surgery was taken in 1559 by a Balkan surgeon called Kasper Stromagyi, who successfully treated a strangulated hernia by incising the skin, ligating the hernia sac at the external ring and then sacrificing the testicle. The wound healed by secondary intension and the patient survived.

140 years later, a German surgeon called Purman treated a second strangulated hernia by similar low ligation of the sac of the external ring. However, Purman spared the testicle, rather than sacrificing it.

These two insights led to sporadic attempts to manage hernia by various attempts to cicatrize the roof of the inguinal canal, typically by burning the aponeurosis of the external oblique with either acid or with hot cautery. As one would expect, the results were absolutely miserable.

The most important advance in the concept of thickening the fascia overlying the hernia bulge came in the mid Victorian era, when another German surgeon called Vinzenz von Czerny treated hernia by suture reinforcement of the roof of the inguinal canal (without having to incise the external oblique aponeurosis and enter the canal itself).

Thus the surgical technique of plication was born and flourished amongst hernia surgeons for a decade or so. However it was abandoned about 10 years later, because general surgeons found that plication had something like a 90% recurrence and 7% septic mortality rate.

By comparison, the concept of plicating the cystocoele was conceived of by Sims just after the American Civil War; however, very little actual treatment of prolapse occurred until a publication by Howard Kelly from Johns Hopkins in the early 1900’s.

Looking at the timelines, it is disappointing that gynaecologists embraced plication of prolapse a quarter of a century after general surgeons had abandoned the technique as being a palliative (not a curative) operation.

Although known to be unreliable, many gynaecologists had kept right on plicating and seem undaunted by the non-curative nature of this surgery.

3. The Era of Anatomic Discovery:

The third era of hernia surgery was driven by the anatomic discoveries of the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1804, Astley Cooper reported that hernia arose secondary to a tearing of the transversalis fascia. Cooper further showed that there were two sites of tearing.

Firstly, there were intrinsic tears within the main body of the transversalis fascia, and

Secondly, the entire fascia transversalis was often avulsed from its normal skeletal attachment to the inguinal ligament and suprapubic ramus.

The net effect of these tears was to disrupt the floor of the inguinal canal.

In this regard, hernia is obviously analogous to prolapse ─ which also has tears within the intrinsic fascia and avulsions from the arcus tendineus in the pelvic sidewall.

Following Cooper’s discovery that tears in fascia transversalis disrupted the floor of the inguinal canal, surgeons now had a valid understanding of the mechanical factors underlying hernia formation. However, they were unable to exploit this knowledge, because any attempt to enter the inguinal canal was beset with surgical misadventure.

Gynaecologists, however, made no progress during this era.

4. The Era of Suture Repair under Tension:

The fourth era of hernia surgery began in 1887, when Geordio Bassini described how ‘site-specific’ tears in investing fascia could be identified and repaired. Bassini’s essential principle was to suture the conjoint tendon and transversalis fascia under tension to the inguinal ligament. Modern hernia surgery had now begun.

Looking at the timelines, hernia surgeons now understood the mechanical aspects of hernia pathogenesis, and had developed a curative operation (with an operative success rate of about 65%). Hernia repair by suturing native tissues under tension held sway for 100 years, from 1887 to the mid 1980s. That is to say, from the time of the steam locomotive to the time of the Voyager space shuttle. During this time, about 70 technique variations on Bassini’s original were described, and operative success rate slowly rose to about 90%.

By comparison, the concept of doing a ‘‘site-specific’’ fascial repair to the avulsed endopelvic fascia as a means of obtaining lasting prolapse repair had been described in the early 1909 by George White. However, gynaecologists were misled by Howard Kelly from Johns Hopkins, into accepting both an erroneous theory and an ineffective treatment for cystocoele and rectocoele. It is disappointing that Kelly’s error occurred some 25 years after surgeons had abandoned palliative plication in favour of a curative repair of the fascia transversalis.

Anterior and posterior vaginal colporrhaphy began on a large scale in the 1920’s, when surgeons like Victor Bonney and Wilfred Shaw returned from World War I.

Richardson re-introduction a mechanically analogous operation for prolapse repair in 1976.

Beginning in the 1990's ,the concept of paravaginal repair is now become widely accepted in North America.

In contrast, European and UK gynaecologists have broadly speaking not embraced Richardson’s concept of paravaginal repair. While there is still a dearth of comparative studies, it is hoped that analogy to the experience gleaned from hernia repair will spur more thought on this issue.

5. The Era of Tension-Free Repair with Mesh:

The era of tension-free mesh repair began with a report by Lichtenstein and Amid in 1984. Nylon darning techniques had been used for recurrent hernias since World War II; this progressed to the use of a patch of woven synthetic mesh by the 1960s. However, the jump to using a mesh overlay for primary hernia was a serendipitous one, when surgeons at a Los Angeles hernia clinic discovered that an open mesh onlay technique greatly reduced postoperative pain (that was mainly due to suture line tension), thereby speeding up the return to normal activity. Surprisingly, this simple and rapid mesh repair method broke through a previously irreducible recurrence barrier, failure rate falling from 10% for ‘suture-only’ operations to <2%>% for tension-free mesh repairs. The reason for these superb results was that using mesh covered both the initial fascial defect and reinforced any weak adjacent tissue. The Lichtenstein open mesh procedure rapidly became the world-wide gold standard.

Looking at the timelines, by 1984, general surgeons had developed an operative technique that resolved both the mechanical and metabolic components of hernia pathogenesis.

By comparison, most gynaecologists were still following Kelly’s erroneous theories on pathogenesis, and were still treating cystocoele and rectocoele by the palliative plication method described by von Czerny in 1877. That is to say, gynaecologists still misunderstood the true mechanical lesion, and remained generally unaware of the secondary metabolic factors that fuel the failure of suture-only prolapse repair.

In car racing terms, prolapse surgeons were now two laps behind!

Some ground was made up in 1982, when Cullen Richardson re-introduced paravaginal repair. However, Richardson’s operation was only a robust Bassini-type tensioned suture repair using native tissue. His advocacy of paravaginal repair (as an alternative to plication) was the equivalent to Bassini’s innovations in 1887. Contemporaneously with Richardson’s pioneering insight, general surgeons were quickly abandoning suture-only repairs, in favour of the Lichtenstein prosthetic hernioplasty.

In other words, gynaecologists following Richardson’s lead were now only one lap behind. To put this another way, general surgeons have been doing tension-free mesh repairs since the time of Ronald Reagan; gynaecologists began tentatively looking at using mesh in prolapse repair in the years spanning George W. Bush’s first term to his second term.

This timeline also shows a 12 to 15 year lag period in gynaecologists beginning to explore tension-free mesh repairs, despite the fact that general surgeons abandoned repair hernias by native tissue brought down under tension.. They also gave up external oblique aponeurosis plication more than 125years ago. Unlike hernia, the principles governing rational tension-free repair of prolapse have not yet been worked out or agreed upon.

6. The Era of Laparoscopic Hernia Repair:

About a decade after the Lichtenstein open mesh repair was introduced, surgeons began approaching hernias through the laparoscope. The initial method, which was an intraperitoneal onlay of mesh, violated the “Hernia Principles” as they had been discovered to that point, and had an unduly high failure rate. However, this error was soon rectified, and there are now two endoscopic methods which do satisfy the “Hernia Principles”. One is called transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) and the other is a totally extra-peritoneal (TEP) repair. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that the open and endoscopic procedures are comparable. Laparoscopic methods have a slightly higher recurrence rate and are somewhat more expensive, for the benefit of about one day earlier return to full activity.

By either technique, general surgeons have brought failure rates down to about 2% for primary hernia and perhaps 5% for recurrent hernia. Relative to prolapse, endoscopy has certainly helped gynaecologists to visualize the existence and location of the little understood ‘site-specific’ defects on the pelvic sidewall. However, durability of laparoscopic paravaginal repair probably falls short of an open APVR.

The Hernia Principles

Let us now look at the Hernia Principles – what they are and how they developed over the 135 years in which surgeons have operated electively.

In the pre- Listerian era, doing elective surgery on non-incarcerated hernias was basically too painful without anaesthesia and too risky in the days before Lister.

The first of these obstacles was resolved by the introduction of anaesthesia in the mid 1840s.

Wells and Morton were two Boston dentists. Wells had used nitrous oxide and Morton used ether. Morton gave the first anaesthesia in Massachusetts General Hospital in 1846.

A year later, J Y Simpson and John Snow (who is ‘the father of epidemiology’ and the person who solved many of the mysteries surrounding cholera), began using anaesthesia in the United Kingdom.

Despite the quite rapid spread of anaesthetic techniques, surgery was basically reserved for emergencies such as amputations, strangulated hernias or obstetric problems. In the pre-antibiotic era, fear of sepsis precluded elective surgery, as illustrated by the fact that there were only 333 operations at Massachusetts General Hospital in the 20 years proceeding the years of general anaesthesia.

Despite the success of anaesthesia, the problem of sepsis remained unresolved. Post operative septic mortality was about 50%, basically because the only hernias that were operated on were those that were strangulated, thus presenting a contaminating field.

The second of these obstacles was resolved by the introduction of antiseptic surgery in the 1870s. Pasteur’s discovery of microbes rationalized medical understanding of sepsis, and Joseph Lister’s invention of an aerosolizing carbolic acid spray that covered the operative field with a fine antiseptic mist dramatically reduced infection rates. With the combination of anaesthesia and antisepsis, the modern era of elective surgery was born. Hernia was one of the first targets of Victorian surgeons. In contrast, prolapse surgery remained a rarity.

First Principle: Avoid Wound Infection.

Over the years, hernia surgery had been dogged by infection, arising initially because operation was usually reserved for incarcerated cases, meaning that surgery was often done in a contaminated field. Even in elective cases, despite the value of carbolic acid spray (and later of aseptic technique), opening the inguinal canal seemed to be a very infection prone operation before antibiotics. In response, the first of the ‘Hernia Principles’ concentrated on how to minimize infection risk through optimal tissue handling.

Important strategies were:

gentle sharp dissection,

use of fine suture,

no mass pedicle ligation and

the strict avoidance of haematoma or seroma.

Subsequent generations of surgeons have learned much of their dissection techniques from hernia repair.

By comparison, many gynaecologists doing prolapse repair are still guilty of blunt dissection with rough tissue handling, mass pedicle ligation, often secured with coarse suture and casual haemostasis with undue reliance on packing. All of this favours microbial colonization of the healed wound and a consequent reduction in the strength in the final repair.

Second Principle: Protect Repair from Intra-abdominal Pressure.

The second principle, which also evolved during the pre-Listerian era, came from the knowledge that the hernia repair had to be protected from intra-abdominal forces. In the pre Victorian era, this was approached by ligating the hernial sac at the external ring.

Later, Bassini and others evolved more secure techniques that involved:

ligating the sac at the internal ring.

narrowing the internal and/or external rings, and

perhaps sacrificing the testicle.

In prolapse surgery, the gynaecological equivalent of this second hernia principle is that we also ligate enterocoele sacs (although perhaps with mesh use, this might not be necessary). Other examples of shielding prolapse repair from abdominal forces are:

uterosacral ligament plication and cul de sac obliteration,

combining prolapse repair with hysterectomy or even colpocleisis,

re-establishing a “hockey stick” vaginal axis, and

narrowing a widened urogenital hiatus.

Third Principle: Repair Tears in Investing Fascia.

Following the work of Bassini, the evolving “Hernia Principles” were extended to include the concept that it is mandatory to repair any mechanical tear in the transversalis fascia. This invariably led to suture line tension. Why is tension such a problem in the Bassini repair? The reason is that it sews together structures that do not normally approximate (ie, the conjoint tendon & fascia transversalis are sewn to the inguinal/Cooper’s ligaments). In consequence, there is pronounced postoperative pain, blood supply is often poor and the approximated structures can pull apart before healing is complete. Hence, the third principle dealt with how to effectively repair the torn investing fascia without exacerbating these healing problems.

Dictates of this principle are that:

the surgeon must sew identical tissue within the same layer,

using interrupted stitches of permanent suture,

without undue suture line tension in any direction.

Basically, placing any kind of suture line in the pelvic fascia produces wound tension regardless of how well the operation is done. However, in doing suture-only repairs, the surgeon must limit the amount of tension created. It is only since the availability of the mesh, 100 years after Bassini’s tensioned repair, that surgeons can avoid wound tension entirely.

The gynaecologic equivalent of the third “Hernia Principle” is the repair of ‘‘site-specific’’ tears within the endopelvic fascia. For example, a high transverse defect, where the pubocervical fascia has separated from the pericervical ring. Obviously, pulling together ill defined “white stuff”, under tension, and constricting the vaginal canal violates these principles. This is an issue that gynaecology as a profession must address.

Fourth Principle: Re-anchor Back onto Skeleton.

The fourth “Hernia Principle” is another legacy of the Bassini’s landmark advances. In addition to repairing the tears within fascia transversalis, Bassini also bolstered the defect by stitching a ‘triple layer’ (which included fascia transversalis) back onto the inguinal ligament. Subsequent surgeons have sometimes used Cooper’s ligament instead of inguinal ligament. No true agreement exists. Both are still used today. By and large the issue has been largely by-passed by the coming of the tension-free prosthetic hernioplasty era.

Gynaecologic equivalents of the fourth principle in prolapse repair are:

Sewing an avulsed lateral margin of pubocervical or rectovaginal fascia back onto the parietal fascia of obturator internus or levator ani muscle. That is to say, repair of a paravaginal defect is really an adherence to the fourth principle, and repair of a superior defect is really an adherence to the third principle.

Likewise, any some form of colpopexy that re-anchors the vaginal vault back onto the uterosacral ligaments, the sacrospinous ligaments or the sacral promontory is another example of Bassini’s fourth “Hernia Principle”.

Obviously, when a gynaecologist purports to “getting good tissue out laterally”, he is not satisfying this hernia repair principle.

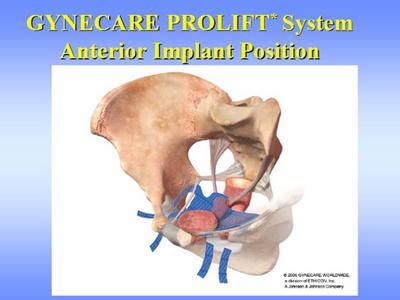

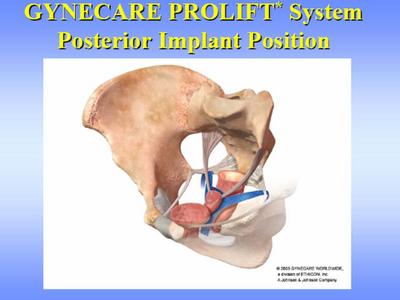

Fifth Principle: Tension- Free Mesh Repair.

The fifth “Hernia Principle” evolved in more recent times, following the introduction of tension-free mesh repair. Recurrence rate of Bassini’s original repair was about 35%; a variety of technique modifications in the first half of the 20th century reduced this failure rate to about 10%. This 10% failure proved an impenetrable barrier, irrespective of surgical skill or precise technique. That is, of course, because the fascial edges being sewn together have a metabolic weakness in their collagen composition, for which some kind of tissue augmentation is the only possible remedy.

The use of mesh in tension-free hernia repairs is now quite well defined:

The mesh must suit the surgical site and the adjacent tissues. In groin hernia, most surgeons prefer low weight, macroporous, monofilament, polypropylene meshes. That is to say, an Amid type 1 mesh.

The mesh must be anchored with interrupted monofilament (not braided) sutures, to prevent subsequent inflammatory reaction from wrinkling the implant into a troublesome mass.

The mesh must also suit the surgical objectives. Is the surgeon trying to reinforce a lateral strut (in which case his repair will only face static forces), or is he trying to bridge a gap between two struts (in which case his repair will be subjected to dynamic forces).

Is the mesh protected from contact with any nearby hollow viscus.

Finally, modern surgeons have learnt that the mesh must be shaped to be tension-free when the patient is ambulatory, not just when they are lying prone on the theatre table. Broadly speaking, this involves keeping the mesh loose (to allow for subsequent contracture), and creating a slight bowl-like curvature within the mesh.

In prolapse, the concept of tension-free mesh repair appears to be equally valid, and I have no doubts personally that it will one day become the norm. However, the principles of mesh use in prolapse are still evolving. I would point out that “the vagina is not the abdomen”, and we cannot ignore these obvious differences.

Abdominal hernias occur in robust collagenous fascia, that lies deep beneath three layers of striated muscle. Moreover, the hernia site is separated from the hollow viscera by the peritoneal membrane and pre-peritoneal fat.

Conversely, prolapse represents a tear in fragile fibrovascular areola tissue, covered only by a thin layer of mucous membrane and lying in close proximity to a hollow viscus. Obviously, vaginal tissues will not tolerate the kind of abrasive tissues reaction that is relatively harmless in the groin.

While there is much debate to be had yet, it is broadly speaking my opinion that biodegradable meshes with remodelling properties are probably preferable to permanent implants.

writen by Dr Richard Reid, Eastpoint Towers,Suite 607, 180 Oceanst, Double Bay, NSW 2028, Australia.